|

This year, with clear evidence that the Trump Administration is jeopardizing many U.S. environmental conservation and protection programs and policies, with hugely damaging consequences, Gary E. Machlis, former National Park Service science advisor (and Clemson University professor of environmental sustainability), and Jonathan B. Jarvis, retired NPS career professional and national director from 2009 to 2017, co-authored an important and inspirational book. The Future of Conservation in America: a Chart for Rough Water (University of Chicago Press) asserts that we are in a period of “rough water,” affecting many environmental assets and conservation programs. The authors identify three major environmental and social threats (and the dangerous irresponsibility of denying them) confronting America: climate change, species extinction, and economic inequality. Actions are required to navigate through the very rough waters facing us. It is essential to assure that the conservation movement is understood by Americans (and especially by young people) as critically relevant to public health and interest. A general re-commitment to environmental conservation and protection is necessary. <<continued>>

2 Comments

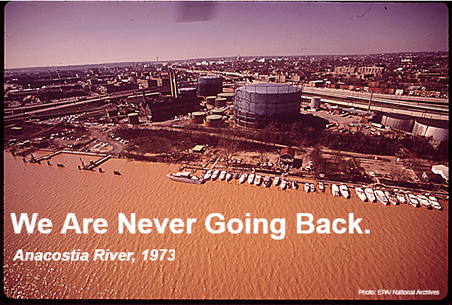

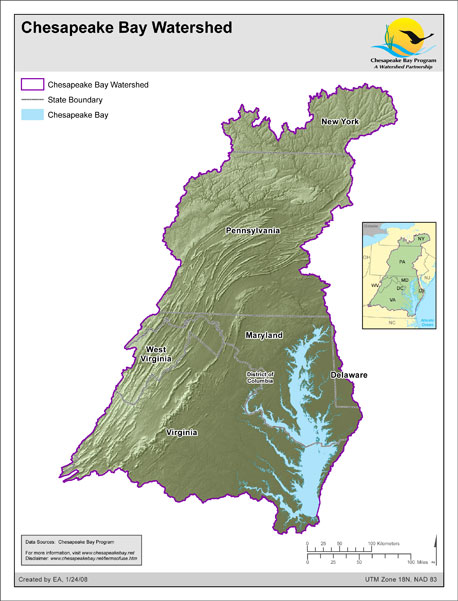

--by Bobby Whitescarver. Note: A different version of this essay was published as an OPED piece distributed by the Bay Journal News Service on October 17, 2017. Read that article here. The Clean Water Act is now 45 years old, born in the U.S. Congress on October 18, 1972. Sometime before that date, the river of my childhood – the Roanoke River in southwestern Virginia – had been declared a fire hazard because of pollution. I learned to water-ski on that river, or rather on one of the manmade lakes along its winding path. It was 1965 and I remember one of those skiing lessons in particular. Dad was the spotter, and his friend George was the driver. I jumped in the water and waited for the handles of the ski rope. When the tips of my skis were up and my butt down, I yelled, “forward!” As the boat began pulling me, I saw banana peels and “floaters” – human waste – drifting past. I was ten years old, and it gave me the heebie-jeebies. “Hit it,” I shouted, now doubly motivated to get up and out of the water. America now has perhaps the best wastewater treatment in the world. . . .  --submitted by by Bobby Whitescarver (originally published in slightly different form here.) The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working to reduce sedimentation and agricultural runoff into streams, make nutrient management simpler and more effective, verify land uses and cover crops via remote sensing, and invest in establishing and maintaining streamside buffers. Lesson 1. The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working Our number one lesson is that the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working. Water quality in the Bay is improving. We have reduced nutrients in the Bay in half since 1983; despite the fact our population as increased 30%. That is quite an achievement. There are many reasons for this. Waste water treatment, application of Best Management Practices (BMPs) on farmland, oyster restoration, air pollution reduction, reductions in phosphorus from laundry detergent and lawn fertilizers, people doing their part . . . I could go on and on. The river that flows through my farm is a TMDL stream (i.e., subject to Total Maximum Daily Loads regulations for polluted streams), and we are in the designated Chesapeake Bay TMDL as well. These designations have brought water pollution and sedimentation control and reduction program funds into our watershed that help farmers install needed BMPs like cover crops, crop rotation to perennials and riparian buffers. Because of these programs our farm now produces food and clean water; something we are very proud of. These programs created jobs for fence builders, tree planters, and other contractors. . . . Partnerships Are Key to Success in Conservation of Land, Water, and Environmental Resources1/19/2017 A basic precept I learned long ago and repeatedly experienced during my forty-year career in land and biodiversity conservation in North Carolina and the southern U.S. confirms that most conservation successes are the result of committed leadership combined with collaborative partnerships among private organizations and public agencies that recognize shared goals and mutual benefits. Seldom have I witnessed a major success in environmental resource conservation that was not achieved through the advocacy of a few dedicated, individual leaders in combination with the support of a coalition of private and public agencies who share a sense of common purpose and mutually held goals. Most successful leaders recognize the power of collaboration and partnership.

But whereas there have been numerous examples of collaborative partnerships among land OR water OR wildlife conservation organizations, coalitions of shared interests across artificial dividing lines between land/water/wildlife conservation have been slower to develop. . . .

Too often we work in self-segregated and uncoordinated isolation in efforts to conserve and protect natural lands and wildlife habitats, rivers and estuaries, public parks and reserved community green places. Failure to coordinate efforts through cooperative alliances diminishes our ability to be effective in aim to protect and conserve more land and water resources.

North Carolina’s environmental protection and land conservation organizations—motivated by the state’s 20-year-old grants program that provides funding for combined land and water conservation projects—have worked together more closely than in many other states, and may serve as an example of how to build partnerships across the South. Until recently,when the North Carolina state legislature and governor drastically reduced funding and combined several of the Clean Water and other environmental trust fund programs, state funding for environmental trust funds in some years exceeded the $100 million annual goal. With the added benefit of privately contributed funds, federal government matching grants, and landowners’ frequent willingness to sell land or easements for conservation at substantially less than appraised value, the leveraging effect of these public funds produced magnificent accomplishments. . . . |

When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.... Conservation, viewed in its entirety, is the slow and laborious unfolding of a new relationship between people and land." There is in fact no distinction between the fate of the land and the fate of the people. When one is abused, the other suffers. From the PresidentSCP President Chuck Roe looked at land conservation along the route of John Muir's "Southern Trek." About ViewpointThis blog offers views of our Board and partners. We invite your viewpoint on the following questions: Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed