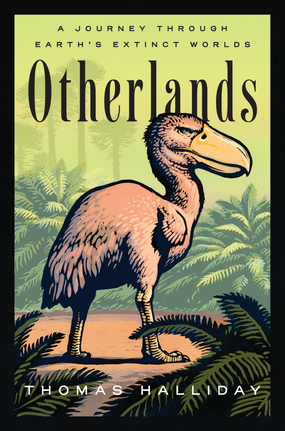

Most of the information and viewpoints found on the Conservation South website focus on issues, opportunities, and resources directly concerned with environmental conservation and restoration in the southern U.S. This book review is different: the topic is a “deep time” perspective. British paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Thomas Halliday has authored Otherlands: Journey in Earth’s Extinct Ecosystems (Penguin Random House, 2022), a fascinating overview of how Earth’s ecosystems and biota have dramatically changed over the long 4-billion-years timeline of life and tectonic forces on our planet. Each of Halliday’s sixteen chapters describes wholesale changes in ecosystems and life forms that have repeatedly occurred throughout eras of Earth history. Earth is now a “human planet,” asserts Halliday, nearly totally affected by we humans. He observes, “The world as it is today is a direct result . . . of what has gone before. Much of life in the past happens in a steady state of slow-changing existence, but there are times when everything can be upended. . . . It is by looking at the past that palaeobiologists, ecologists and climate scientists can address the near- and long-term future of our planet, casting backwards to predict possible futures. Unlike past occasions . . . our (human) species is in an unusual position of control over the outcome (of a fundamentally altered biosphere). We know that change is occurring, we know that we are responsible, we know what will happen if it continues, we know that we can stop it, and we know how. The question is whether we will try.” <continued . . .> Life will survive. "(L)ife has survived through Snowball Earth and poisoned skies, meteoric impacts and continental-scale volcanoes, and the recent world is as diverse and spectacular as it ever was. Life recovers, and extinction is followed by diversification. That is, in a way, a comfort, but it is not the whole story. Recovery brings radical change, and often startlingly different worlds, into being, while also taking, at minimum, tens of thousands of years. Recovery cannot replace what has been lost. When we compare our world with that of the end-Permian (the era of the Pangea supercontinent, 252 million years ago), we can find some worrying similarities” (with our present time). Dramatic global warming and rapid climate change, decline in atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels, intense releases of carbon from fossil fuels and peatlands and permafrost decomposition, carbon acidification of seawater, melting glaciers, instable atmospheric and ocean currents, horrifyingly rapid declines in the biomass of wildlife and accelerating rates of species extinctions, explosion of the human population numbers and the impacts of human overpopulation and our wastes. The effects are cascading. "We are also introducing new ecosystems. Perhaps the modern equivalent to the post-extinction ecosystems. . . . The survival of a species is about more than the environmental tolerance of an individual’s physiology. It relies also on the resilience of its behaviours. There is no corner of the Earth where we have not touched the way of life of its inhabitants in some way. . . . The planet is beginning to resemble a post-extinction world." Halliday attempts to end on a hopeful note, saying, "But we must not become despondent. Human-induced change is, in itself, not new, and, to a large extent, can be considered natural. We are part of the biological realm, inhabiting the tree of life. There is solid evidence that humans, like so many species that have come before us, have always been ecosystem engineers…. We are such effective ecosystem engineers that the idea of a pristine Earth, unaffected by human biology and culture is impossible. Such an Eden simply does not and, since the emergence of humans, never has existed. While the damage that is being done to global ecosystems in unprecedented in our species’ lifetime, conservation programs need to decide what degree of human impact is desirable and achievable…. "Today, we can see the changes that are about to unfold. The geologic history of our planet paints, in broad but unmistakeable brushstrokes, a picture of possible futures. We are undergoing a humanitarian and natural disaster that encompasses the whole planet, but it is something we can manage…. Only by altering our habits (overcoming the inaction of complacency and ‘business as usual’ approach) and by endeavoring to live less exploitatively, can we prevent the changes to the environment from becoming an unparalleled catastrophe, another Great Dying” [as occurred at the end of the Permian age]. In his conclusion, Halliday appeals: For our long-term well-being as a species and as individuals, we must enter into a more mutualistic relationship with our global environments. Only then can we preserve not just their infinite variety, but also our place within them. Change, eventually, is inevitable, but we can let the planet take its own time, as we allow the shifting sands of geological time to lead us gently into the worlds of tomorrow. Sacrifice--an act of permanence. Then, we too will live in hope.” --Chuck Roe, President, Southern Conservation Partners

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.... Conservation, viewed in its entirety, is the slow and laborious unfolding of a new relationship between people and land." There is in fact no distinction between the fate of the land and the fate of the people. When one is abused, the other suffers. From the PresidentSCP President Chuck Roe looked at land conservation along the route of John Muir's "Southern Trek." About ViewpointThis blog offers views of our Board and partners. We invite your viewpoint on the following questions: Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed